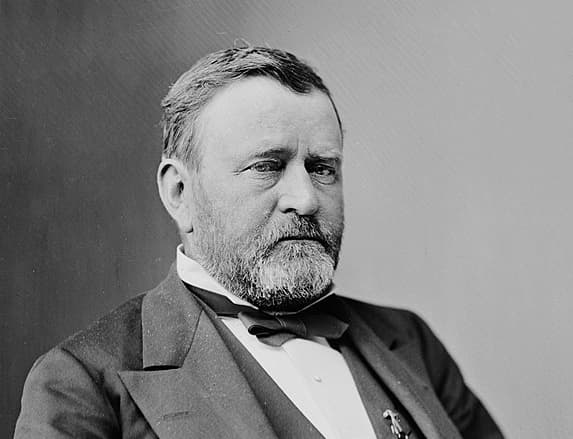

General Petraeus Headlines Celebration of the Birth of U. S. Grant

Just in the nick of time, America did find out what Grant was drinking, and it turned out to be the draught of liberty.

Tonight, the Grant Monument Association celebrates the 201st anniversary of President Grant’s birth at the Union League Club at New York City. Headlining the dinner on the Civil War general’s ascendant legacy is a four-star Army general, David Petraeus.

The association’s president, Frank J. Scaturro, was a student at Columbia University in the 1990s when he saw that, like General Grant’s reputation, the monument on Manhattan’s Hudson River Shore — final resting place of the two-term president and his wife, Julia — had fallen into disrepair.

Homeless people squatted inside, and Satanic cults desecrated the sarcophagi. Mr. Scaturro volunteered to help the National Park Service and, as a guide, pushed for more funding, writing a letter to President Clinton exposing the filthy state of what’s known as Grant’s Tomb.

When press coverage shamed the park service, they fired Mr. Scaturro, but as I discussed with Louis Picone in the History Author Show interview about his book, “Grant’s Tomb: The Epic Death of Ulysses S. Grant and the Making of an American Pantheon,” a renaissance began.

“Grant’s monument,” a sponsor of tonight’s event, Catherine Windels, told me, “was renovated, just turned around completely. It reopened parts of it that had to be closed. It was cleaned and everything was much, much better — and it’s really due to Frank.”

Mr. Scaturro founded the Grant Monument Association, and its Grant Day Dinners raise money for the monument’s upkeep and Grant education. Mr. Petraeus attends each year along with a Grant biographer like this year’s guest, Brooks Simpson.

In a 2017 interview with a professor from the Thunderbird School of Global Management, Jeffrey Cunningham, Mr. Petraeus praised Grant’s “sheer will, indomitable determination, and quiet fortitude,” calling him a “near genius as a tactical leader, an operational leader, and a strategic leader.”

Before the Grant Monument Association, Grant was viewed in a less kind light, lost in a crowd of bearded, Gilded Age faces just as — even while commanding the Union Army — the quiet and humble man had gone unrecognized at the White House and when checking into a Washington D.C. hotel.

Mr. Petraeus tells the story of Grant sitting alone in the rain, waiting for the sun to rise, after being caught short on the Battle of Shiloh’s first day. His right hand general, William Tecumseh Sherman, Mr. Petraeus said, “comes out of the dark and says, ‘Well, Grant, we had the devil’s own day today, didn’t we?’”

“Yep,” Grant replied, and then, without a hint of the defeatism that had characterized other Union generals, said, “Lick ‘em tomorrow, though,” and so they did. In recognition of those displays of greatness, Congress promoted Grant to six-star General of the Armies of the United States last year. That puts him on a par with but two others — George Washington and John J. “Black Jack” Pershing.

As Grand Army veterans passed away, Grant devolved into the caricature of a drunk who hadn’t won the Civil War so much as his Confederate counterpart, Robert E. Lee, had lost it. At 5’8” and 135 pounds, Grant was what we’d today call a lightweight, but he triumphed over the bottle as he did other obstacles throughout his life.

When complaints about Grant’s drinking were brought to Lincoln, the president replied: “Find out what he’s drinking and get some to the rest of my generals.” Or words to that effect.

What defined Grant is his determination, not his drink. “He habitually wears,” a military staff officer, Theodore Lyman, wrote, “an expression as if he had determined to drive his head through a brick wall, and was about to do it.”

The Civil War generation recognized Grant’s service to the country not just in battle, but in binding up the nation’s wounds after the guns fell silent. His words following Lee’s surrender, chiseled over the entrance to his monument, read not of vengeance but reconciliation.

“Let us have peace,” Grant said, but he didn’t seek to buy that domestic tranquility, as so many did, by selling out freed African Americans. As president, he crushed the Ku Klux Klan, stopping efforts by Southern Democrats to win through terrorism what they’d lost on the battlefield.

After Grant’s death, defeated Confederates flipped the maxim that winners write the history, but the GMA helped put Grant back where he belongs. Today, he stands where he belongs atop America’s pantheon of heroes, a reminder that no matter how bad our problems get, we can always lick ‘em tomorrow.