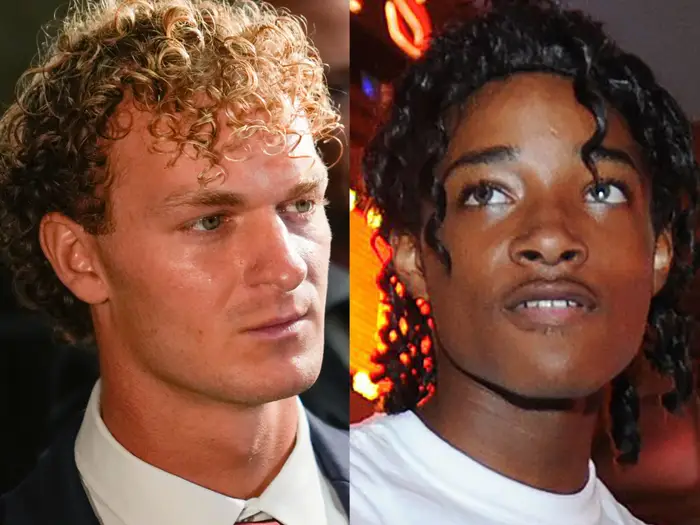

Daniel Penny’s Trial Tests Whether New Yorkers Have Lost Patience With ‘Defining Deviancy Down’

What stands out in respect of the Penny case is how many commentators have suggested that Jordan Neely’s behavior was unexceptional and just part of the daily fabric of New York City life.

The trial of Daniel Penny, accused of killing a homeless man, Jordan Neely, is bringing into sharp relief issues far beyond Penny’s guilt or innocence. They recall Senator Daniel Moynihan’s essay from 1993, “Defining Deviancy Down,” in which he grappled with the problems of crime and social disintegration increasingly prevalent in urban America during the prior decades.

According to Moynihan, society was always willing to tolerate a certain level of crime, provided that it could be controlled and kept at that level. A community’s tolerance of crime, or deviance, was measured by the apparatus it put in place to accomplish such control, including the police, courts, and prisons. What society would tolerate was a function of public policy.

However, the situation might arise where the level of criminality exceeded the resources of the system. Under that circumstance, Moynihan wrote, a community would be faced with a choice: it could “afford to recognize” the number of offenders in its midst and augment the law enforcement apparatus necessary to control them, or it could simply “choose not to notice behavior that would be otherwise controlled, or disapproved, or even punished.”

As an example of the latter, Moynihan referenced New York’s approach to the mentally ill and, by extension, the homeless. In 1955, mental patients numbered more than 90,000 in New York state alone (approximately ten times today’s number), overwhelming its capacity to house them.

Five years later, Moynihan, as part of a committee established by President Kennedy to address the problem, recommended the release of most patients coupled with funding for two thousand community mental health centers to assist in the patients’ transition back to society. Needless to say, the patients were almost all released, but only a fraction of these centers was ever funded, let alone built.

The result was inevitable. Failing to provide the necessary structure to treat the mentally ill, New York, as policy, chose “not to notice” the resulting behavioral consequences. Homelessness was neither controlled nor disapproved.

With Mr. Penny’s trial, Moynihan’s thesis has reached a particular flashpoint, playing out in full view in a New York City courtroom. According to pre-trial testimony, shortly before he was killed, Neely paced around the subway, coming within inches of passengers.

While doing this, he shouted, “someone is going to die today,” “I want to hurt people.” More recently, at trial, a witness testified that Neely raised his fists and yelled that, if not given food and water, “he [was] gonna start putting hands on people,” and that “[h]e was going to start attacking,” and another quoted Neely as saying: “I will kill a motherf–ker.”

What stands out with respect to the Penny case is not whether he is innocent or guilty, about which I offer no opinion, but how many commentators have suggested that Neely’s behavior was unexceptional and just part of the daily fabric of New York City life. For example, a writer for the New York Times argued that Neely was just “making people uncomfortable.”

Another Times writer, Elizabeth Spiers, mocked the idea that anyone might be fearful in such a situation, tweeting: “I’ve safely ridden the subway for 23 years and my child has never been menaced by a half-naked lunatic, but these imaginary monsters in your head are addressable with therapy.”

More significantly, these sentiments have moved from the opinion pages to the Penny trial itself. Prosecutor Dafna Yoran expressly acknowledged how unremarkable it is for New Yorkers to confront individuals like Jordan Neely, suggesting, according to one report, that Neely’s “erratic behavior is something that New Yorkers can witness daily.” She added: “As New Yorkers, we train ourselves not to engage. Not to make eye contact. To pretend people like Jordan Neely are not there.”

Although intended as a rebuke, Yoran’s argument was an inadvertent admission that Moynihan’s thesis remains durable thirty years on. She merely substituted “Choose not to notice” for “pretend he is not there,” while chastising New Yorkers for adopting as private policy what the City long ago adopted as public policy.

Tuesday’s election suggests that, as a whole, the country is losing patience with policies such as this. Even California demonstrated a shift in sentiment when passing, by a large majority, Proposition 36, which largely reversed the decriminalization of shoplifting. One wonders whether New Yorkers will ever lose patience.