Can the Stormy Daniels ‘Zombie’ Case Land Trump in Jail? It’s Quite a Stretch

The Manhattan district attorney will have some startling hoops to jump through in bringing a case against President Trump.

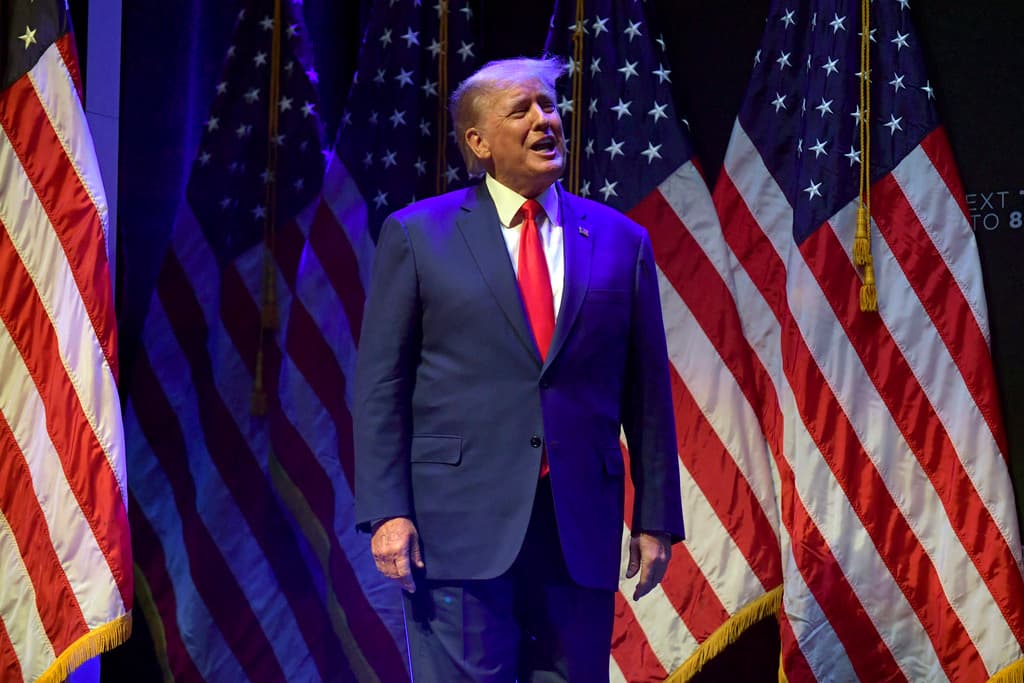

Given the legal storm clouds surrounding President Trump — they stretch from Mar-a-Lago to Georgia’s Fulton County to Washington, D.C., to New York — an indictment can hardly come as a surprise. Manhattan now appears to be the likeliest bet to supply the first charges against a former president.

That possibility has elicited wrath from the usual quarters, including from Mr. Trump himself, Speaker McCarthy, and, after a two-day delay, Governor DeSantis, widely seen as Mr. Trump’s primary threat for the 2024 GOP presidential nomination. Steel barricades are being erected in Lower Manhattan in advance of possible protests over an indictment.

What is unexpected, though, is the starring role played in all this by a humble species of crime — the misdemeanor. While the charges stemming from the alleged payments to a porn star, Stormy Daniels, are not yet known, speculation focuses on a possible prosecutorial pirouette, with the misdemeanor for starters.

Should the Manhattan district attorney, Alvin Bragg, hand up an indictment, Mr. Trump will have to defend himself against a newfangled combination, a chimera, a beast of incongruous parts appended to a case from long ago. The payments were made in 2016, and prosecutors will have to keep an eye on statute of limitations.

The theory goes something like this: In New York, falsifying business records is a misdemeanor, punishable by up to a year in jail, though a more likely punishment is community service or probation or both; however, if falsification is accompanied by “an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof,” it can be stepped up to a felony.

To pull this off against Mr. Trump, Mr. Bragg’s prosecutors will have to show that the former president possessed both the “intent to defraud” as well as the culpable state of mind to use that offense as a means to pursue a second crime, likely connected to campaign finance violations.

Even the experts have seen nothing like it. A professor of criminal law, Anna Comisnky, tells the Sun this is a “novel theory” of culpability that has hitherto not been tried in a New York courtroom. Much the same point was made in these pages by Alan Dershowitz, who termed these prospective charges “novel and unprecedented technical crimes.”

“Misdemeanor” comes from the French for “bad behavior,” and its difference from a felony is not metaphysical but practical. A misdemeanor is defined in American law as a crime whose punishment is less than a year. If punishment involves more than one of Earth’s trips around the sun, the crime is considered felonious.

While a president has never been criminally charged, the Constitution does contemplate misdemeanors in relation to the chief executive. Article II Section 4 ordains that the “President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

Mr. Trump will know this language well, as he has been twice impeached under its terms. He was determined to be “not guilty” in both instances. However, unlike misdemeanors in the criminal code, Joseph Story’s “Commentaries on the Constitution” explain that “no previous statute is necessary to authorize an impeachment for any official misconduct.”

The language of “high crimes and misdemeanors” was imported from across the Atlantic, its phrasing bearing a timestamp as far back as 1386, when the King’s chancellor and first earl of Suffolk, Michael de la Pole, was impeached. Alexander Hamilton, in 65 Federalist, wrote that England was the “model from which the idea” of impeachment was borrowed.

Current events were likely close to mind for Hamilton, as in 1787, as the Constitution was being debated at Philadelphia, the philosopher and parliamentarian Edmund Burke was leading famous impeachment proceedings against the governor general of Bengal, Warren Hastings, for crimes against “those eternal laws of justice” that were “in substance and effect, High Crimes and High Misdemeanors.”

Mr. Trump appears set to contest not “those eternal laws of justice,” but Mr. Bragg’s application of the criminal code in novel forms. The burden of proof will lie in the end on only the district attorney, who will have to convince a jury of Mr. Trump’s peers — and fellow New Yorkers — that a misdemeanor is sturdy enough a peg to bear the weight of a president’s conviction.