Boris II: Johnson Could Emerge as a Serious Statesman

He invented himself as a prime minister like no other — a comedic genius but an effective parliamentarian.

It was with relief and gratitude that I received a request from the principal editor of this publication to write about the vote amongst the members of the British Parliament in the governing Conservative Party to sustain Prime Minister Boris Johnson. By historic standards, it was far from a rousing vote of confidence.

The vote was 211 to 148, a substantially poorer level of approval from his fellow Conservatives than Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain received in May 1940, when 50 of his fellow conservatives voted against him and 41 abstained in a vote of the entire House of Commons, which convinced him that he did not command an adequate level of confidence to try to lead Britain any farther through the Second World War, which was beginning as badly as it could.

Two days later Winston Churchill, a veteran of 39 years in the House of Commons and nine different cabinet positions under five prime ministers, was called upon by King George VI to form an all-party national unity government and preside over a war cabinet to which virtually all powers except taxation were delegated.

Fortunately, while these times have their challenges, they are hardly comparable to “the Finest Hour” of 1940, and the support of nearly 60 percent of his fellow Conservative M.P’s is adequate to sustain the prime minister, though the defection of 41 percent of his M.P.’s cannot fail to be seen as a serious storm signal. Mr. Johnson has been warned.

The principal ostensible argument against Boris Johnson is that while his government was enforcing a severe Covid shutdown regime in Britain, he hosted dozens of garden parties at his official residence where alcoholic beverages were served and masking and social distancing were not observed. Of course, this is pretextual nonsense; people in high public offices are substantially exempted during crises from the same constraints that are applied to the public.

Mr. Johnson was holding farewell parties or parties to reward with a little normal conviviality people who had worked extremely diligently in the government to deal with a public health crisis that was without recent precedent. The anti-Johnson press vividly portrayed the contrast with the selfless conduct of the nonagenarian Queen Elizabeth II, sitting alone at the funeral service in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, for her husband of 74 years, Prince Philip.

Tear-jerking reporting was lavished on the fact that there was apparently a Christmas celebration in the prime minister’s residence while such occasions were generally restrained among the public. These were minor indiscretions that would not have raised questions of confidence in the government were it not for two factors unique to Johnson: although polls now indicate that a substantial majority of the population of the United Kingdom is glad that the U.K. is no longer wholly integrated into the European Union, the “Remainers” who lost a referendum of 2016 by a hair’s breadth are still fueled with hate and venom.

The civil service, leaders of British industry, the British press, the political establishment, academic opinion: an unholy alliance whose existence, antics, and tactics are familiar to any observer of contemporary American politics, seized whatever they could to try to effect a bloodless assassination of the man who sliced the Gordian knot, and resolved the crisis that was the greatest spectacle of parliamentary incompetence in British government since the American Revolution, if not the English Civil War. That 17th century conflict ended with the decapitation of King Charles I and the dictatorship of Oliver Cromwell.

Boris led the Thatcher Conservatives who opted for the American alliance and closer association with the advanced Commonwealth countries (especially Canada and Australia) over submergence into Europe, and his opponents followed Prime Ministers Harold Macmillan, Edward Heath, and David Cameron away from the alliance of the leading English-speaking countries where Britain was of necessity second to the United States, and into the top tier of Europe, where it was claimed that Britain, France, and Germany would lead a united Europe back to a preeminent influence in the world such as existed prior to the First World War.

Yet the institutions of British government that have evolved gradually and relatively peacefully over a thousand years were to be subordinated to the factory of authoritarian directives spewed out by unaccountable European commissioners in Brussels, and the mighty tradition of British diplomacy, from Wolsey and Chatham, Castlereagh, Palmerston, Disraeli, and Churchill would be subsumed into the Davos-man-like quest for a world of socialistic, climate-obsessed homogenization of the European Union.

Obviously the issues are more complicated than these caricatures, but ultimately the choice was between Britain operating as a sovereign state in the whole world with traditional closely related allies, and Britain as an important but very much minority component of a Europe attempting in admirable good-faith but with certain and conspicuous difficulty to find a common policy stretching from Portugal to Bulgaria and Finland and from the Arctic to Cyprus.

It was a protracted and bitter struggle that immobilized for years a Parliament that in 2017 was best summarized on the front page of the London Daily Mail after another complete parliamentary impasse with the headline, over a photograph of the Westminster Parliament: “House of Fools.” So it was, and for delivering the country from that, Boris Johnson has brought down upon himself the implacable hostility of much of the most influential section of British opinion.

The other unique factor is that Boris Johnson himself is a former journalist who has attracted the acidulous envy of the journalistic craft because of his extraordinary self-projection from journalism to the mayoralty of London to foreign secretary to the leadership of Britons who wished to leave the EU to prime minister. The British are a good deal more envious than Americans and less uplifted by a culture of meritocratic achievement.

In addition, there are legitimate policy problems: inexplicably, but perhaps as a tactical sop to red Toryism and the ubiquitous eco-lobby, Mr. Johnson has gone cock-a-hoop for the green madness, and he has committed the unconservative misstep of raising taxes to help pay for the comprehensive National Health Service. Universal healthcare, instituted 75 years ago is a matter of irrational pride in Britain, and in fact the NHS is rivaled only by the BBC as the greatest sacred cow in the country, but raising taxes to help pay for it was a political and fiscal mistake.

Boris Johnson invented himself: he is a prime minister like no other, in Britain or elsewhere; a comedic genius but an effective party leader and parliamentarian. His shtick, though, has been worn threadbare. It is time for him to brush his hair properly, speak generally without clever Oxford quips, double entendres, and almost slap-stick clowning.

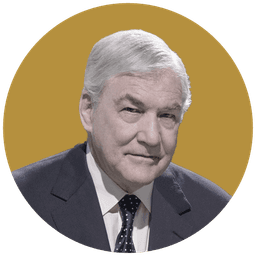

Boris Act I confounded his opponents and scandalized his critics, but after great success has now brought him close to the brink. It is time for Boris Act II, effective statesman. I was for many years his employer and had the privilege of assisting him in becoming extremely famous and of helping to launch his political career.

I am proud of having done so, and I’m confident that the best is yet to come and that we will not have long to wait for it. The true Boris Johnson has been the West’s outstanding and most effective leader in the Ukraine war. The United Kingdom and the West need him.