Biden: The Road Not Taken

The president promised a return to normalcy and bipartisanship. In the event, though, he took a different route.

There’s a parable about a land of two tribes — one always tells the truth and one always lies. A visitor is trying to get to the capital of this strange land when he comes to a fork in the road. A gentleman in local dress is standing there. The visitor wants to ask him which fork leads to the capital. He must, though, be careful. He doesn’t know if the local is from the tribe that always lies or the one that always tells the truth. So what question can he ask?

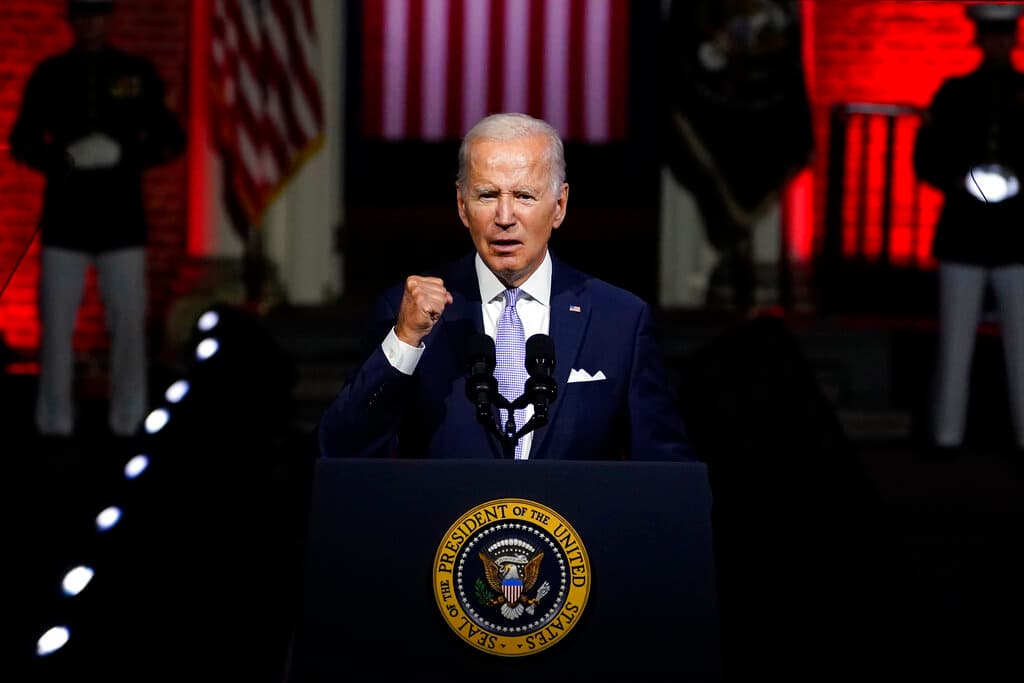

We’ve been thinking of this puzzler as we reflect on President Biden. How did he make his decision on what road his presidency would take? He promised a return to normalcy and bipartisanship. In the event, though, he took a different route. It has delivered what could be the most bitterly divided America since the Civil War. This is inflamed by his decision to pursue criminal charges against, in President Trump, his leading challenger for re-election in 2024.

What a contrast with, say, President Ford. He acceded at a bitter time. He chose a unifying course, pardoning his predecessor, Richard Nixon. It might, or might not, have cost him the presidency. Jimmy Carter defeated him in 1976. The day was saved by one of the great unifiers, President Reagan. He brought the country together in 1980, winning 44 of the 50 states, and in 1984, taking 49 of the 50 states. Only Washington* did better.

Then, too, of course, there’s Lincoln. He led the country in its most divided moment only to summon, at Gettysburg, our better angels. At a time when the outcome of the Civil War was still undecided, he offered a message of reconciliation as opposed to rancor. Of the soldiers who had died there he called for America to re-dedicate itself to “the great task remaining before us” so “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.”

Lincoln saw that the stakes in that conflict were existential for America’s democracy and that the war would decide whether “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” By 1865, when the Union’s victory was assured, he called in his second inaugural for magnanimity, urging “malice toward none with charity for all” as the means to “bind up the nation’s wounds.”

So Lincoln offered generous terms of pardon for the Confederates. When General Lee surrendered at Appomattox, the rebel army was not prosecuted but sent home on their word never again to take up arms against the Union. When celebrations broke out among the federal troops, General Grant ordered them to stop, saying, “The war is over; the rebels are our countrymen again,” and so “the best sign of rejoicing” was “to abstain from all demonstrations in the field.”

As for Lee, his acceptance of the Confederates’ defeat, as opposed to continuing to fight a guerrilla war, spared the nation what could have been years of bloody conflict. We don’t want to make any inapt comparisons. Yet nearly a century later, in 1960, Richard Nixon refrained from challenging the narrow election result that handed the presidency to JFK — despite questions about voting fraud, especially at Chicago.

“We won,” Nixon griped privately to his friends in the aftermath of the election, “but they stole it from us.” Yet Nixon was aware that contesting the results would spark what he called a “constitutional crisis” and “tear the country apart” — not to mention open him to “charges of ‘sore loser,’” historian David Greenberg has explained. So Nixon opted against challenging the outcome — a course that would have put Mr. Trump in a better position today.

Which brings us back to Mr. Biden’s bitterness. Mr. Trump’s alleged wrongdoing left plenty of room for prosecutorial discretion. Mr. Biden’s choice to prosecute his political rival can only worsen the divisions in America, which has become a land in which neither side trusts the other. Hence the yarn about the land of liars, where those seeking a true answer have to ask, say: If we were to ask you tomorrow how to unify the country, what would you say?

_________

* President Monroe ran unopposed.