Biden Could Follow Obama in Using the UN To Settle Scores With Israel

Rather than threatening to veto an anti-Israel UN resolution, the American ambassador there is negotiating its language.

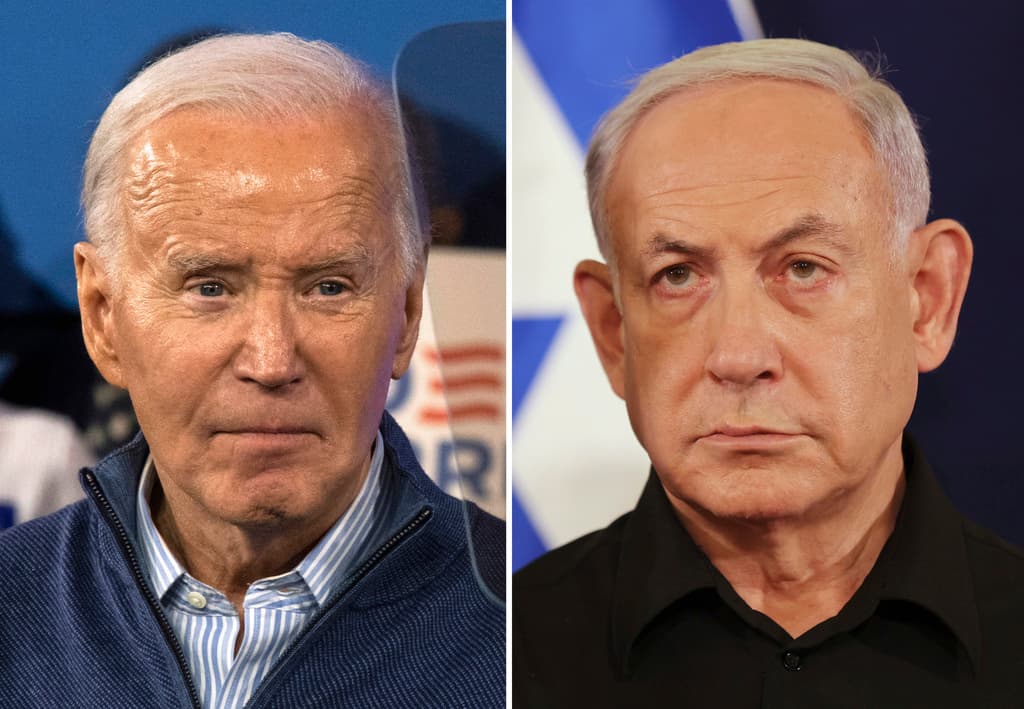

Will President Biden use his remaining time in office to settle old scores, including with a world leader who has long rankled him, Prime Minister Netanayhu? If so, the United Nations would be the perfect venue for a revenge move.

The fraught relations between the American president and the Israeli premier might have worsened on Election Day, when Mr. Netanyahu fired his defense minister, Yoav Gallant, who has long been the White House’s most trusted Israeli official.

Mr. Netanyahu on Wednesday morning was one of the first world leaders to call and congratulate President-elect Trump. After a similar call to Mr. Biden in 2020, Mr. Trump cursed the Israeli leader. If any bad blood remained between the two like-minded men, though, it was likely erased after they spoke at length about Mideast issues Wednesday.

Meanwhile, in the twilight of his presidency, Mr. Biden might consider a repeat of President Obama’s act of revenge against Mr. Netanyahu. In December 2016 the American UN ambassador, Samantha Power, abstained on an anti-Israel resolution at the UN Security Council. Mr. Biden might do the same.

The Security Council is weighing a proposed resolution, which is already endorsed by most of the council’s 15 members, that calls for an immediate Gaza cease-fire. The Israeli ambassador, Danny Danon, who calls the proposal “biased,” tells the Sun that it’s the first time a council resolution “does not mention the most important condition for a cease-fire, which is the release of all 101 hostages.”

Rather than threatening to veto it, though, the American UN ambassador, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, is quietly negotiating its language. Diplomats say Washington might acquiesce, or, alternatively, initiate a separate resolution.

On Wednesday at the General Assembly a host of speakers denounced the Knesset’s recent legislation to end Israeli cooperation with the UN Relief and Works Agency. Mr. Danon on Monday formally notified the UN of the termination. The Department of State condemned the Israeli law, but only nine of the 120 Knesset members opposed it.

Mr. Biden could of course consider non-UN routes if he wants to express his anger at Mr. Netanyahu. He could issue an executive order that would diminish the premier’s already-plummeting political support at home. Such an order, though, would be short-lived, as Trump would likely rescind it on January 20.

Mr. Biden might alternatively consider cutting a deal with the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed Bin Salman, that would leave Israel behind. Riyadh’s national security adviser, Musaad bin Mohammed al-Aiban, visited the White House last week to discuss a defense treaty with the U.S., which would be “separate from an Israeli mega-deal,” Axios reports.

A U.S.-Saudi defense treaty combined with the establishment of full relations between Riyadh and Jerusalem was nearly completed last year. Talks were mostly suspended after Hamas’s October 7, 2023, massacre. Completing the deal now without Israel would certainly sting Mr. Netanyahu, who mentions the need to widen the Mideast peace circle in almost every speech.

Yet, shortly after the Israeli premier called Trump on Wednesday, Prince Mohammed also called. Both the Saudi and Israeli leaders have cultivated deep ties with the president-elect, his aides, and his family members. Jerusalem and Riyadh will likely await Trump’s inauguration before making any major move to please the outgoing president.

At the UN, in contrast, most resolutions cannot be undone by the next American president. Here, anti-Israel acts are widely applauded. That was likely Mr. Obama’s calculation in 2016, when he facilitated and declined to veto a Security Council resolution that redefined American policy on Israeli settlements and declared Jerusalem an “occupied territory.”

Addressing the General Assembly on Wednesday, the Unrwa chief, Philippe Lazarrini, said that the Knesset legislation “poses an imminent and existential threat to the agency.” He urged UN members to lean on Israel to rescind it. Secretary-General Guterres piled on, reminding in a letter that Israel is “obligated” to cooperate with the aid agency.

In 2020, Trump cut funding to the agency, which was tainted with Hamas ties. Mr. Biden resumed payments, but they were cut again this year by Congress after Israel documented the participation of Unrwa employees in the October 7 massacre.

Ms. Thomas-Greenfield spoke against the Knesset legislation, though, telling the Security Council that Washington has “deep concerns” about it and arguing that “there is no alternative to Unrwa.” A Jerusalem diplomat tells the Sun that America might now use the aid agency as a foundation for a Security Council resolution that could later lead to sanctions against Israel.

“Is Unrwa a hill we now want to die on?” a European diplomat credulously asked the Sun Wednesday. Even after Congress cut aid to the tainted agency, Mr. Biden seems to be embracing a positive answer to that question.