Before Special Prosecutor Takes on Trump, He Could Move To Disqualify Judge Cannon

The judge who appointed a special master, only to face appellate wrath, is back in charge of the Mar-a-Lago criminal case.

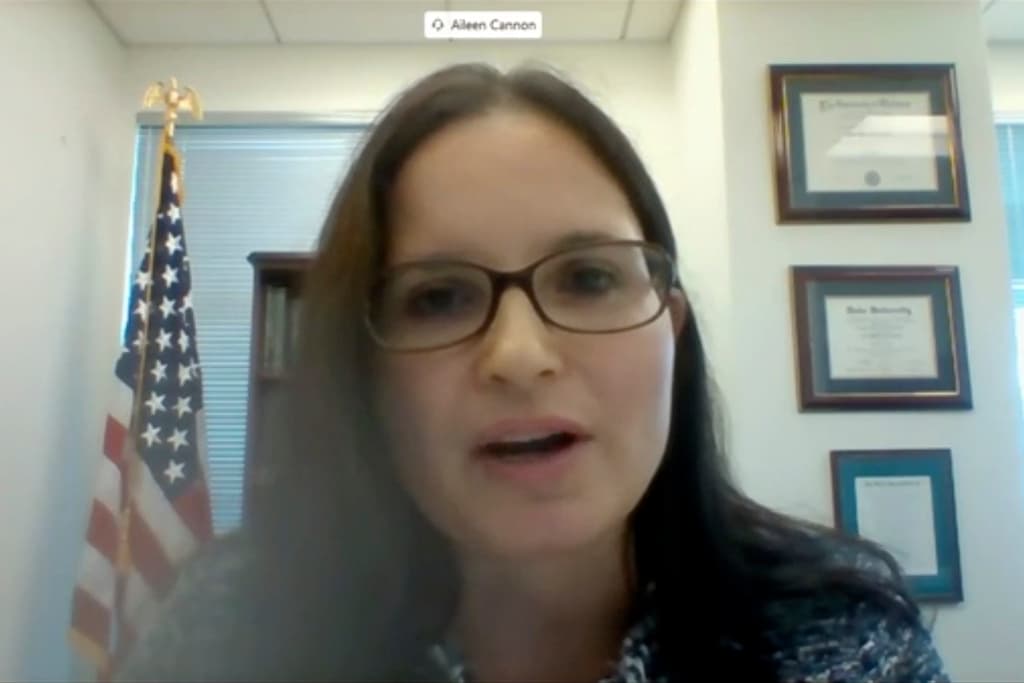

The assignment of a Florida district court judge, Aileen Cannon, to oversee Special Counsel Jack Smith’s case against President Trump presents the former war crimes prosecutor with a strategic choice — does he move to have her taken off the case?

Mr. Smith’s team is likely mulling that move because Judge Cannon, who was appointed by Mr. Trump, has already made her presence felt at an early stage in the investigation into documents discovered at Mar-a-Lago, when she ordered the appointment of a special master and halted the Department of Justice’s pre-indictment work.

Judge Cannon’s handling of the previous case — and her freeze of the investigation and appointment of an outside superintendent to comb through the evidence against Mr. Trump — was roundly rejected by a panel of the 11th United States appeals circuit, which issued a stinging rebuke and ended her custody of the case. Now, if Mr. Smith persuades them, those riders could remove her again.

While Judge Cannon will likely not be present for Mr. Trump’s initial appearance at a Miami courthouse on Tuesday, it appears as if the case now belongs to her. A magistrate judge, Jonathan Goodman, will be on the bench for the preliminary formalities. The chief clerk for the Southern District of Florida has said the selection of Judge Cannon was random, the product of a computerized lottery.

The special counsel has likely reviewed Judge Cannon’s decision that temporarily banned prosecutors from “further review and use of any of the materials” seized at the Palm Beach manse “for criminal investigative purposes.” President Trump appointed Judge Cannon to the bench in November 2020, just before he left office.

Judge Cannon appeared to be sympathetic to Mr. Trump’s argument that his status as a former president means that the search at Mar-a-Lago was especially inflammatory and politically pyrotechnic. She wrote that his “former position as President of the United States, the stigma associated with the subject seizure is in a league of its own.”

The circuit riders lambasted the decision to freeze the government’s ability to review the documents discovered at Mar-a-Lago, accusing Judge Cannon of “a radical reordering of our case law” that was crosswise “bedrock separation-of-powers limitations.” They criticized what they called her effort to “carve out an unprecedented exception in our law for former presidents.”

Federal law ordains that a judge “shall disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” Partiality need not be proved. Instead, even an appearance of partiality, if it possesses a reasonable foundation, is enough to push a change in judicial personnel.

The Supreme Court has held that recusal is in order when “an objective observer,” drawn from the public at random, “would have questioned” the judge’s impartiality. If that bar is met, a judge’s failure to recuse herself is a “plain violation” of the law. A request for recusal would have to be submitted first to Judge Cannon herself, and then could be appealed.

The 11th Circuit has articulated its own standard for when a judicial reassignment is demanded. In a 2006 case, United States v. Martin, a healthcare executive, Michael Martin, who pleaded guilty to “massive and prolonged fraud summed to billions of dollars,” was given seven days in jail in lieu of the recommended sentence of 108 to 135 months. The riders mulled whether the “extremely lenient sentence the district court gave is reasonable.”

In remanding the case back to the district court for a second sentencing, the appeals court also ordered a new judge be appointed, citing “two reversals in this case and three other appeals in which we have reversed the same judge for extraordinary downward departures that were without a valid basis in the record.”

The circuit, while acknowledging there was no “actual bias,” found that if a judge is not able to set “previous views and findings aside,” he must step aside. Glossing this precedent, Mr. Smith could argue that the Judge Cannon’s previous exposure to the Mar-a-Lago matter, and to the 11th Circuit’s wrath, is disqualifying.

Judge Cannon, though, behaved differently than the judge who was removed in U.S. v. Martin. In the question of the special master, Judge Cannon did promptly comply with the 11th Circuit’s ruling. Getting reversed by an appeals court, after all, it is not an uncommon experience for a judge, nor, in and of itself, a result of bias.

Mr. Smith is himself no stranger to the ability of appellate judges to review and reverse. In 2014, when he was chief of the Department of Justice’s Public Integrity Section, he secured a conviction of the governor of Virginia, Robert McDonnell, and his wife for corruption. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit affirmed.

The Supreme Court, though, in a stunning and unanimous opinion, overruled that judgment and found that the prosecutors had convicted the McDonnells for deeds that weren’t illegal. Chief Justice Roberts wrote: “There is no doubt that this case is distasteful; it may be worse than that. But our concern is not with tawdry tales of Ferraris, Rolexes, and ball gowns. It is instead with the broader legal implications of the Government’s boundless interpretation of the federal bribery statute.”

In other words, prosecutors, as well as judges, can suffer stinging setbacks.