Back to School Means Back to Court for Title IX Sexual Assault Cases

‘We’re ending a period where schools were forced by the Education Department to treat accused students fairly,’ a history professor who studies college sexual assault cases tells the Sun.

As college students head back to campus this fall, major changes to Title IX regarding how schools handle sexual misconduct allegations are on the horizon — and with those changes will likely come a wave of new lawsuits.

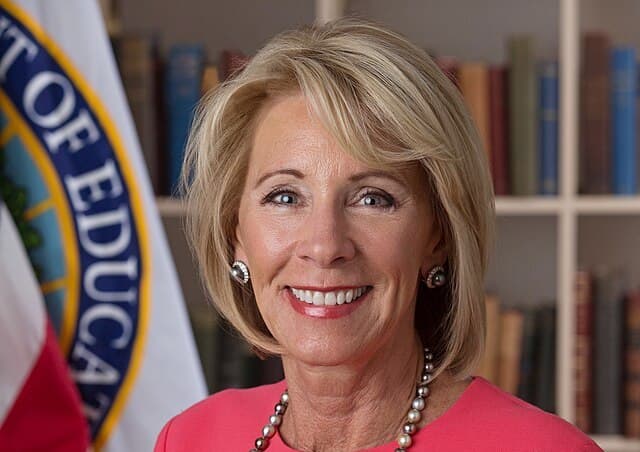

The Biden administration’s Title IX rule changes, which are slated to be released in October, will reverse many of the Trump-era Title IX rules instituted while Betsy DeVos was education secretary and revert to guidelines similar to those laid out in the Obama administration’s 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter.

Among these changes — spelled out in a more than 700-page document that was released in 2022 and has since undergone a process of comment and review — is the elimination of students’ right to live hearings, to cross-examine involved parties and witnesses, and to representation by attorneys in cases of sexual misconduct.

This means that a student accused of sexual assault will not have the right to face an accuser, either in person or virtually. Instead, a school administrator can decide to weigh the “credibility” of each party through separate questioning and come to a determination that way. Under these new rules, a college Title IX coordinator can function as the investigator, the judge, and the jury in these cases.

The Biden administration changes, if the final rules conform to the proposed ones, will also expand the definition of sexual harassment and weaken the standard for determining guilt from “clear and convincing” to a “preponderance of the evidence.” In essence, they will lower the bar for reaching a guilty verdict in what are often “he said, she said” cases.

“We’re ending a period where schools were forced by the Education Department to treat accused students fairly, and we’re going to return to what was a pre-2020 era, where the only defense for a wrongly accused student is going to be the courts — you know, found guilty by your school and then suing in the aftermath,” a Brooklyn College history professor who studies college sexual assault cases, KC Johnson, tells the Sun. “There will just be a wave of new litigation by accused students.”

Title IX of the Education Amendments is a 1972 law that prohibits sexual discrimination in school programs that receive federal funding. It governs athletics as well as the adjudication of cases of sexual harassment and assault in schools.

The current Title IX rules regarding college sexual assault were instituted in 2020 under President Trump. These rules sought to correct what the administration saw as a scale tipped too far in favor of the accuser. The prior rules, instituted during the Obama administration, were designed as a sweeping “new paradigm” to tackle “rape culture” on college campuses, but they led to more than 600 lawsuits — many of them successful — from accused students arguing their due process rights had been violated.

The Trump administration’s Title IX rules narrowed the definition of sexual harassment and guaranteed accused students the right to face and cross-examine their accusers, as well as to be represented by attorneys. These rules sought to “continue to combat sexual misconduct without abandoning due process,” Ms. DeVos said at the time.

The rules, though, were controversial. Sexual assault survivor groups and activists criticized the Trump administration’s Title IX changes as too onerous for victims and protective of the accused. The Biden administration says that the 2020 changes led to a decrease in sexual assault claims and had a “chilling effect” on victims reporting abuse.

“The 2020 Title IX Regulations narrowed protections and created monumental barriers to reporting,” a legal services provider for sexual assault victims, the Victims Rights Law Center, wrote in a statement. “Survivors who went through a Title IX process at their institution often experienced a grueling process that ended with a multi-day live hearing with cross-examination.”

The Biden administration’s new rules are “for the most part, a reversal back” to the Obama administration’s, the legislative and policy director for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, Joe Cohn, tells the Sun. “A lot of political promises have been made,” he says, and the education department’s Office of Civil Rights “is staffed by true believers.”

The #MeToo fervor of 2017 has faded to some extent — President Biden had his own accuser, and “believe all women” has lost some credibility after several high-profile cases were later proved to be false accusations — yet the Biden rule changes are a throwback to this time. While espousing the principles of fairness, the overarching goal — laudable in principle — is to make it easier for women to come forward and have their cases adjudicated in college “trials.” This is achieved, though, by stripping due process protections from the accused.

The problem now is there is a body of case law from prior Title IX lawsuits that affirms accused students’ rights to live hearings and cross-examination. As an example, Mr. Cohn points to the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals’ 2018 decision in Doe v. Baum, et al., in which the court ruled that college sexual assault cases require live hearings and cross-examination. He says the Biden administration’s Title IX changes will thus create a “patchwork” of different procedures across the country.

“Until we start prioritizing the rights of everyone and giving that time to take hold, you’re going to continue to have litigation,” Mr. Cohn says. “It’s not exactly a great thing that now it will actually be binding rules that strip due process protections out of the process, or at the very least, give schools the green light to do so.”

Another prominent case making its way through the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals is Saifullah Khan v. Yale University, et al. The case stems from a 2015 accusation of rape made by a Yale University student, Jane Doe, against a fellow Yalie and scholarship student from Afghanistan, Saifullah Khan.

Mr. Khan was acquitted of all sexual assault charges in a criminal court in 2018, yet Yale later found him liable at the college’s sexual misconduct proceeding and expelled him. Mr. Khan is now suing Yale and his accuser for $110 million in a defamation lawsuit.

In late June, the Connecticut supreme court, which the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals had asked to review the case, ruled unanimously that Ms. Doe was not immune from defamation charges while testifying at Yale’s Title IX sexual misconduct hearing because the hearing did not meet “quasi judicial” standards and therefore did not offer immunity protections of a court. At issue was that Mr. Khan could not cross-examine his accuser or call witnesses, and that Ms. Doe was not required to testify under oath.

“The Connecticut supreme court held that Yale’s procedures represented a kangaroo court and were no court at all,” Mr. Khan’s attorney, Norm Pattis, tells the Sun.

“There was just no interaction, no cross examination, no ability to do really anything,” Mr. Khan tells the Sun. “At heart what makes something judicial is fairness. … With Yale, I was just guilty Day One.”

The attorney for Jane Doe did not return the Sun’s request for comment.

If the 2nd Circuit remands the Khan defamation case back to district court to be decided on the merits, Mr. Khan’s suit could have chilling implications for colleges. If they scrap live hearings, they could open themselves up to similar lawsuits.

In an interview with the Sun, Mr. Khan says that the #MeToo fervor at Yale, the fact that he was a scholarship student from a Muslim country, and that 77,000 persons had signed a petition to have him removed from campus all played into Yale’s decision to find him liable. He says that colleges are fundamentally incapable of adjudicating cases fairly because their institutional interests will always trump justice.

He says the ultimate goal of his lawsuit is “to get colleges out of this crime adjudication business.” He has undisclosed financial backers with “aligned interests” helping him.

“I don’t think Khan is wrong that there is a fundamental atmospheric problem that permeates with institutions adjudicating these cases,” Mr. Cohn says. “In a perfect world, institutions of higher education would not have this responsibility to do these adjudications and investigations because they’re not particularly equipped to do it well.”

“They tend to do what’s in their best interest with, you know, if it’s the star quarterback who’s accused or one of their wealthiest donors who buildings are named after, the incentives might be just to sweep it under the rug,” Mr. Cohn says. “But when it’s the average student, getting the federal government off [the college’s] back, or the bad press for being accused of harboring a sexual predator, is a powerful incentive.”

We don’t live in a “perfect world,” though, and Mr. Cohn says the goal now should be to set rules that protect victims and those accused in equal measure. He says the Biden administration’s proposed changes are a step in the wrong direction.

“We should be taking very seriously everyone’s rights, because there are people who are innocent and there are people who are guilty, and we need to do justice by everyone and try to get that question right as often as we can,” Mr. Cohn says.

Plus, he adds, if a Republican wins in 2024, the whole process of changing Title IX regulations will start again. In the meantime, the major actions will be in the courts.