As January 6 Committee Seeks a Prosecution of Trump, the Issue of Double Jeopardy Emerges in Sharp Relief

Can a president who was acquitted — declared ‘not guilty’ — by the Senate be tried again in any court?

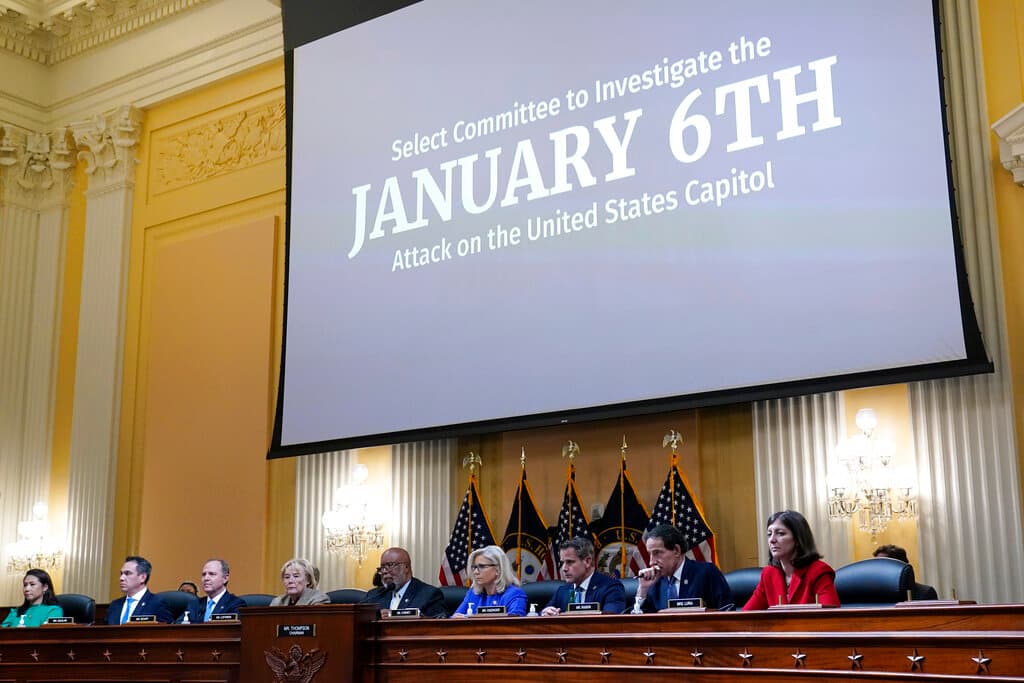

When on Monday morning the cameras click on for the second public hearing of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol, the resemblance to a legal rather than a legislative proceeding likely will not be just uncanny, but undeniable.

More than just Americans at large, the audience for the committee’s work appears to be Attorney General Garland. It is his Justice Department that will ultimately decide whether to bring charges against President Trump, or anyone else.

Since the hearings began on Thursday, calls for criminal indictments based on the committee’s work have accelerated, with Representative Adam Schiff urging the Department of Justice to “investigate any credible allegation of criminal activity on the part of Donald Trump.”

As talk of indictments and prosecution heats up, one constitutional question is starting to come into sharp relief — the prohibition against double jeopardy. The parchment’s Fifth Amendment states that no person shall “be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb.”

Double jeopardy stands for the idea that irrespective of whether a verdict is guilty or innocent, a person cannot be tried a second time on the same criminal charges. This does not apply to charges brought up by the state and federal governments, as they are considered independent sovereignties.

The committee, whose staff is stocked with federal prosecutors, is intimately familiar with the nature of those deliberations. Two of the committee’s highest-profile members, Representatives Schiff and Jamie Raskin, led the impeachment trials against Mr. Trump.

Mr. Schiff has not been shy about urging the executive branch to apply itself, noting “there are certain actions, parts of these different lines of effort to overturn the election that I don’t see evidence the Justice Department is investigating.”

Any such investigation will occur in the shadow of Mr. Trump’s second impeachment, whose sole article included “incitement to insurrection” and “lawless action at the Capitol,” overlapping with the events that the committee has spent months pondering.

The outcome of that trial — a legal and political hybrid designed by the Founders — was an unambiguous verdict of “not guilty.” It may be that a majority of the senators, 57, voted to convict. That, though, is far short of the constitutionally required supermajority of 67.

That experience, in which Mr. Raskin spearheaded the prosecution, is likely what prompted him to promise that the committee will be able to demonstrate “a lot more than incitement.” Speaking at Harvard University’s commencement, Mr. Garland vowed “we will follow the facts wherever they lead.”

There is, though, a startling feature of the Constitution’s language in respect of impeachment. While impeachment proceedings have the accoutrements of a trial, including the chief justice of the United States presiding and the Senate sitting as jury, a guilty verdict does not activate the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition against double jeopardy.

That amendment’s language has been read broadly by our courts as prohibiting double jeopardy for any crime. If one is convicted in an impeachment and removed from office, though, the Constitution allows for a second trial in a regular court.

“Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States,” is how the Constitution puts it, “but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.”

That second trial is available, though, only to “the Party convicted.” This raises the question of what happens if the party — like Mr. Trump — is acquitted. That is, was discovered by trial in the Senate to be, in fact, “not guilty,” as the Senate pronounced it. In this case, is the government empowered to try in regular court a person who was acquitted in an impeachment?

An attempt to bring charges against Mr. Trump in connection with insurrection could well be the first time this question has been presented. None of the three presidents who have been impeached — Andrew Johnson, William Clinton, and Donald Trump — were tried in criminal court after their conviction.

While the legal consensus is that an impeachment trial is not a legal proceeding of the nature that evokes double jeopardy, it is also true that the committee is sailing into uncharted constitutional waters, a route that may eventually lead to a Supreme Court challenge.

Even as the committee aims to convince Mr. Garland to take action to move Mr. Trump’s case from the House to a courtroom, its seven Democrats and two Republicans appear to be striving to hold the attention of the nation at large.

“President Trump summoned the mob, assembled the mob and lit the flame of this attack,” Representative Elizabeth Cheney averred at the first hearing, but it will be up to the committee on which she serves to keep the embers burning for an America being challenged right now militarily in Asia and Europe, tested over immigration on our southern border, and in a monetary crisis over the collapse in the value of the dollar.

So holding the national interest will be a challenge for the January 6 committee. A Friday report showed inflation surging, with the May consumer price index hitting its highest level since 1981. Prices have risen 8.6 percent year over year, and 6 percent when excluding food and energy prices. The Dow plunged 800 points in response.

Economic malaise has precipitated political murmurings. The New York Times canvassed Democratic insiders for an article titled, “Should Biden Run in 2024? Democratic Whispers of ‘No’ Start to Rise.” The portrait painted is one of a party fretting over its aging leader with ever greater anxiety as crises mount from the Donbas to the gas pump.

President Obama’s chief strategist, David Axelrod, expressed worry to the Times over “the stark reality is the president would be closer to 90 than 80 at the end of a second term.” He labeled that “reality” a “major issue.”

The committee certainly appears to have engaged a significant audience. Nielsen reports that more than 20 million viewers tuned in Thursday night, roughly the equivalent of a presidential debate or an installment of “Sunday Night Football.” The next four hearings will be daytime affairs, with the final one, on June 23, returning to prime time.

Understanding that members of Congress are more familiar with bloviating than broadcast, the committee retained a one-time president of ABC News and producer of “20/20,” James Goldston. Under the hand of the television maestro, the initial hearing ran just one minute over two hours.

Will the audience be there for the followup? The committee has previewed Monday’s hearing as one that will show that “Trump engaged in a massive effort to spread false and fraudulent information.” Whereas Thursday focused on conjuring the events of January 6 itself, this one will attempt to tell its prehistory.

On the menu for Monday is Mr. Trump’s campaign manager during the 2020 election, Bill Stepien, as well as Chris Stirewalt, a political editor for Fox News during the 2020 election. On that night in November, Mr. Stirewalt called Arizona for Mr. Biden, eliciting consternation from Mr. Trump in the process.