A New King and Prime Minister Confront an Old English Challenge

In these early days of their reign and premiership, both the new king and the relatively young premier will find their agendas defined in part by Irish questions.

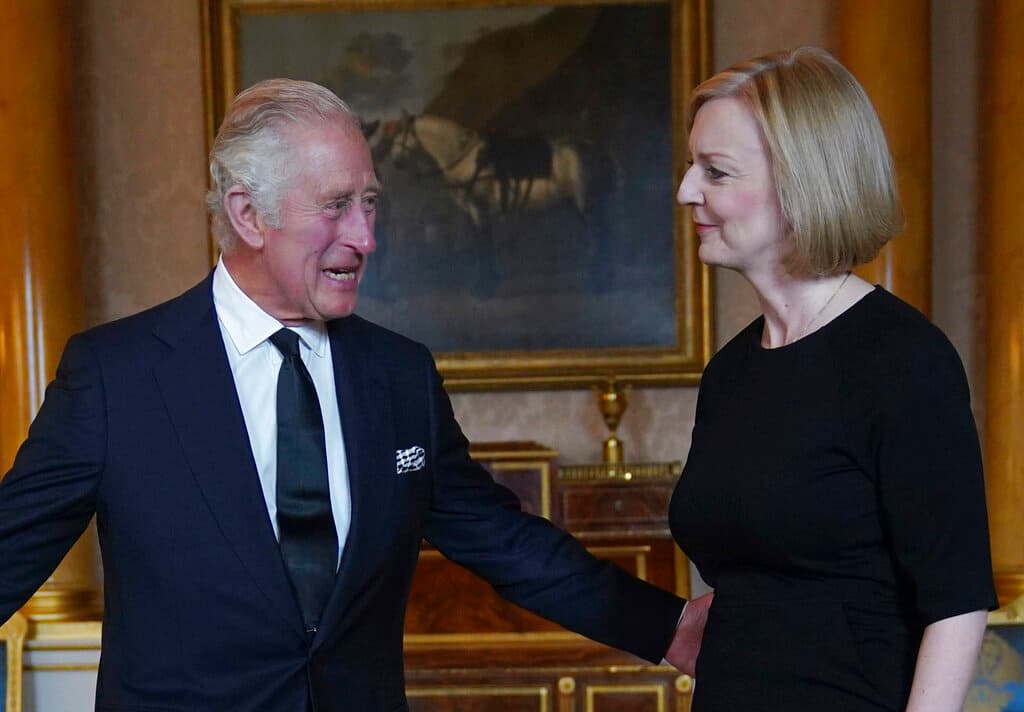

The sovereign, King Charles III, will travel to Belfast on Tuesday to accept condolences from some of the crown’s loyal subjects as well as its most vociferous critics. The new British premier, Elizabeth “Liz” Truss, will meanwhile be tasked with working out a problem bequeathed to her by Prime Minister Johnson: Dealing with Northern Ireland.

In these early days of their reign and premiership, respectively, both the elderly king and the relatively young prime minister will find their agendas defined not only by looming economic headwinds but by one of Britain’s oldest challenges, its relationship with its neighbor to the west. That is one that vexed the first Elizabeth as well as the second.

By many accounts, the most successful trip of Queen Elizabeth II’s seven-decade reign was to Ireland in 2011. She began her remarks at Dublin Castle in Gaelic, a surprise to her hosts, who did not expect Queen Victoria’s great-great-granddaughter to intone, “A Uachtaráin, agus a chairde,” or, “President and friends.” The republic’s flags were lowered to half mast at her passing.

The history between England and Ireland makes such warmth nothing short of improbable. In 1169 of the common era, Anglo-Normans flooded in from England and conquered Ireland, beginning 800 years of English and British domination. A papal bull from the only Englishman to sit on the throne of St. Peter, Adrian IV, gave religious imprimatur to the new rulers. It was only in 1922 that the Irish Free State was born.

Elizabeth reigned for three decades of the Troubles that haunted the North, but also wore the crown when the Good Friday accords brought peace. Nevertheless, Elizabeth’s security arrangements were the most expensive ever undertaken by Ireland. Her cousin, Lord Louis Mountbatten, was assassinated aboard a fishing boat by the Irish Republican Army in 1979.

While in that speech at Dublin the queen acknowledged “our troubled past” and “things which we would wish had been done differently or not at all,” it is the future of Northern Ireland — itself tied into the knotty arrangements of a post-Brexit future between England, and Europe — that appears set to preoccupy Prime Minister Truss.

While she was Mr. Johnson’s foreign minister, Ms. Truss took a hard line on the Northern Ireland protocol, the arrangement reached by Mr. Johnson that seeks to align the open-border principles of the Good Friday Agreement with the realities of Brexit. Ms. Truss has pushed for Parliament’s ability to unilaterally revoke the protocol, a position that the European Union maintains would violate international law.

All eyes are now on whether Ms. Truss will seek to trigger the protocol’s Article 16, an emergency measure that allows unilateral action if either the U.K. or EU feel that the protocol has engendered “economic, societal or environmental difficulties.” Ireland’s foreign minister, Simon Coveney, has said that Ms. Truss “has had the opportunity and has been asked by some to trigger Article 16 before, and she hasn’t done it.”

Another path toward changing the protocol runs through domestic law rather than the text of the agreement itself. The Northern Ireland Protocol bill, which has been wending its way through Westminster, would neutralize its effect in domestic law and allow ministers wide latitude regarding its implementation.

America has weighed in as well, with the White House press secretary, Karine-Jean Pierre, sending the message on Ms. Truss’s second day in office that “efforts to undo the Northern Ireland protocol would not create a conducive environment” to negotiate a trade pact between the U.K. and America.

The debates over the protocol at Westminster will transpire against the chaotic backdrop of a breakdown in Northern Irish politics. Following a springtime victory by Sinn Féin in the Stormont Assembly, the Democratic Unionist Party, fiercely pro-Brexit, has boycotted the executive, ensuring that it does not function until their demands to revise the protocol are met.

For its part, Sinn Féin, long the vehicle of Catholic beliefs and republican aspirations, harbors hopes of a united Ireland and a recovery of the six northern counties that stayed attached to the United Kingdom after the War of Independence. It has scheduled a “People’s Assembly” for October 12 as part of an ongoing “Commission on the Future of Ireland.”