A Kaddish for Lord Balfour

More than a century ago the future British foreign minister hears Chaim Weizmann speak the mind of millions — and today comes an attack on Balfour’s portrait.

The slashing of the portrait of Lord Balfour at Trinity College, Cambridge, is a shocking development. Not since the Taliban destroyed the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001 have we seen such an act. The destruction of the portrait of Balfour was especially shocking, given the antisemitism that has engulfed Britain and emerged at the center of the war against the Jewish state, in the creation of which Balfour played such a prescient part.

Balfour was foreign secretary of Britain when, in 1917, he signed what is known as the Balfour declaration. The declaration was made in a letter to Baron Rothschild, a leader of British Jewry. Balfour’s aim was to signal that Zionism would be among the causes rewarded in World War I. A few years ago in these columns, we described the letter as one of the most consequential three-paragraph notes ever written.

It was penned 11 years after Balfour’s first meeting with the Zionist Chaim Weizmann, who would become Israel’s first president. They met at a hotel at Piccadilly. Balfour was then running for Parliament. They fell into a conversation about Theodor Herzl and a plan to settle Jews in Uganda. “Mr. Balfour,” Weizmann, a chemist by trade, said, “supposing I were to offer you Paris instead of London, would you take it?”

Balfour replied: “But, Dr. Weizmann, we have London.”

“That is true,” Weizmann responded. “But we had Jerusalem when London was a marsh.”

Balfour leaned back and eyed the chemist. Then he said: “Are there many Jews who think like you?”

That’s when Weizmann uttered the immortal words: “I believe I speak the mind of millions . . .”

The ensuing letter would change the world.

“His Majesty’s government,” it declared, “view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

Balfour described that statement as a “declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations.” At the time the Great War was still in progress. The League of Nations had yet to be brought fully into being. Nor had it granted Britain the mandate over Palestine. The letter, though, was not nothing. It has drawn the ire of the enemies of the Jews for decades. An apology from Britain has been sought, but Britain has courageously demurred.

The furor over the Balfour Declaration, though, has long underscored the rejectionist nature of the Palestinian Arab agitation. This, we’ve noted before, was marked several years ago at Jerusalem by Prime Minister Netanyahu. He spoke of how the call for an apology for the Balfour declaration was driven, as Breitbart News quoted him, “not by territorial dispute but by the very existence of the Jewish state.”

Mr. Netanyahu is quoted by Breitbart as saying the demand for an apology disclosed “the true source of this enduring conflict.” It is “not about territory, even though that’s an issue. It’s not about settlements, even though that’s an issue. It’s not the issue. It was never and is still not about the Palestinian state. It was always about the Jewish state.” That is the object of the hatred that drives Israel’s enemies. Balfour died in 1930.

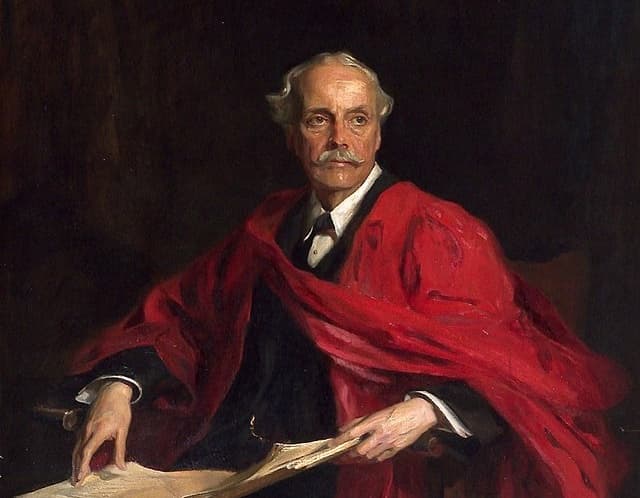

Hence this modest editorial kaddish, a prayer of exaltation of God often recited in mourning. Balfour, our Jordan Esrig reports, was the subject of 140 portraits. The one destroyed today was by Philip Alexius de László, one of the greatest portrait painters of his time. We pray that his painting will be restored and protected for centuries to come. And that Balfour’s family, heirs, and admirers will be comforted among the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem.